Habitat Fragmentation: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

Habitat fragmentation is a critical environmental issue that affects ecosystems worldwide.

Research shows that over 70% of global forests are now located within just 1 km of their edges, exposing them to the degrading impacts of fragmentation.

This process not only reduces biodiversity by up to 75% but also disrupts essential ecosystem functions like nutrient cycling and biomass production.

The most severe effects are seen in the smallest and most isolated habitat fragments, where damage compounds over time.

This article explores habitat fragmentation in detail, covering its definition, causes, and far-reaching effects on ecosystems and biodiversity.

What is Habitat Fragmentation?

Habitat fragmentation is the process of dividing a continuous habitat into smaller, more isolated patches, often separated by human-modified landscapes. While natural events like wildfires or volcanic eruptions can sometimes cause fragmentation, it is primarily driven by human activities.

Common causes of habitat fragmentation include:

- Development and construction: Building roads, highways, and urban areas can divide habitats into smaller pieces.

- Mining: Extracting minerals or other resources can destroy or fragment habitats.

- Logging: Clearing forests for timber or other purposes can create fragmented landscapes.

- Agriculture: Converting natural habitats into farmland can isolate remaining areas.

- Urban sprawl: The expansion of urban areas into rural regions can fragment habitats.

A simple example of habitat fragmentation is a road cutting through a forest. This road effectively divides the forest into two smaller fragments, isolating them from each other. As the road network expands, it can further fragment the habitat, creating more edges and reducing the size of core areas.

What Are the Effects of Habitat Fragmentation?

Habitat fragmentation has significant and often negative consequences for ecosystems and biodiversity. These effects can be categorized into several key areas:

Biodiversity Loss

When large habitats get divided, many species struggle to survive in smaller, fragmented patches. Some animals, like large predators or species with specialized needs, require vast territories to hunt, breed, or find food. As their habitat shrinks, their populations can plummet.

For example, big cats or elephants that once roamed across large landscapes now find themselves boxed into smaller areas, with limited food or mating options. Eventually, this can lead to local extinction, reducing overall biodiversity.

Species that need highly specific conditions—like certain plants that rely on particular pollinators—may completely disappear from a fragmented habitat.

Interrupted Ecological Processes

Nature relies on connected ecosystems to function smoothly. Take seed dispersal as an example: animals like birds or mammals often carry seeds across long distances, helping plants spread.

In fragmented habitats, those animals might not be able to travel between patches, which means seeds don’t get spread as widely, limiting plant regeneration.

Similarly, pollinators like bees or bats may struggle to move between fragmented areas, reducing the chances of plants being pollinated.

Fragmentation can also affect nutrient cycles, soil health, and even water filtration in ways that might not be obvious immediately but are harmful over time.

Increased Edge Effects

Fragmentation creates more "edges" where the habitat meets a different landscape (e.g., where a forest meets a road or field).

The conditions along these edges—more sunlight, wind, and exposure—are vastly different from the stable, protected interiors of ecosystems. Edges tend to favor invasive species or generalists that can tolerate harsher environments.

In forests, for instance, trees at the edges might face more intense sun and wind, making them more vulnerable to disease or storms. Meanwhile, animals adapted to deep, quiet forests might find it impossible to survive on the noisy, disrupted edges.

Isolation and Genetic Decline

Species populations that are cut off from one another due to fragmentation can no longer interbreed as easily. This isolation leads to a reduction in genetic diversity, which makes species less adaptable to changes in their environment, such as disease outbreaks or climate shifts.

Over time, this genetic bottleneck can result in inbreeding, weakening the health of the population. A well-known example is the Florida panther, whose population was so fragmented and small that it experienced genetic defects due to inbreeding, including heart problems and reproductive issues.

Changes in Species Interactions

When habitats get fragmented, species that once coexisted harmoniously may end up in direct conflict, or predators and prey might no longer encounter each other as frequently.

For instance, in smaller, isolated patches, top predators may disappear because the area can no longer sustain them.

This can cause a "trophic cascade," where the removal of a predator allows prey populations, like deer or rodents, to grow unchecked, which then over-consumes vegetation, destabilizing the entire ecosystem.

Displacement and Increased Stress for Wildlife

As natural habitats shrink, many animals are forced into areas where they would normally avoid human activity, such as farms, suburbs, or roads.

This displacement leads to higher mortality rates from vehicle collisions, conflict with humans, or exposure to unfamiliar predators.

Animals like bears or wolves, who need large territories, often end up wandering into human settlements, where they are seen as a threat and sometimes killed.

Even less obvious forms of stress—like constant exposure to noise, light, or pollution—can take a toll on wildlife health and behavior.

Human-Wildlife Conflicts

With fragmentation bringing wildlife closer to human activities, conflicts are on the rise.

Elephants, for example, might wander into agricultural fields in search of food after their habitat is cut off, leading to crop damage and retaliation from farmers.

Similarly, animals like deer or raccoons may come into urban areas, causing nuisance or posing risks, like vehicle accidents. These conflicts put additional pressure on already struggling wildlife populations.

Facilitation of Invasive Species

Fragmented landscapes create opportunities for invasive species to spread. Invasive plants, animals, or pathogens often thrive in disturbed environments.

Roads and other infrastructure can act as corridors for these species, helping them move into fragmented habitats where they outcompete native species.

For instance, invasive plant species may take root at the edges of forests, altering the soil composition and light availability, which disrupts the native plant community.

Similarly, invasive predators like rats or feral cats can easily penetrate fragmented habitats and prey on native wildlife, especially on islands.

Changes in Microclimates

When large habitats are broken into smaller patches, the environmental conditions within these patches change dramatically.

Forests, for example, have cooler, more stable climates deep inside. But when they are fragmented, the exposed edges face hotter, windier, and drier conditions.

This change can make life difficult for species adapted to the cooler, humid interior.

Amphibians, like frogs, that rely on moisture may find it harder to survive in these altered microclimates.

Similarly, plant species that need consistent shade might struggle in sun-exposed fragments.

Barriers to Migration

Many species need to migrate to find food, mate, or respond to seasonal changes. Fragmented landscapes, however, create physical barriers to movement.

For example, highways, cities, or agricultural lands can block animals from moving between different patches of habitat.

This becomes especially problematic with climate change, as many species will need to shift their range to cooler areas.

If animals can’t migrate due to habitat fragmentation, they are more likely to suffer and potentially go extinct. Large mammals like caribou or birds like migratory songbirds are particularly vulnerable to these movement barriers.

Impact on Ecosystem Services

The services that ecosystems provide, like water purification, carbon storage, and soil fertility, can be heavily impacted by fragmentation. For instance, forests play a critical role in sequestering carbon from the atmosphere.

However, smaller, fragmented forests are less efficient at doing so. Similarly, wetlands and intact forests help filter water and prevent flooding.

When these areas are fragmented, their ability to perform these vital ecosystem services diminishes, potentially leading to more frequent and severe flooding, water contamination, and loss of agricultural productivity.

What Are Real Life Examples of Habitat Fragmentation?

A common example of habitat fragmentation is the construction of highways through large, continuous forests. Initially, a single road may split a forest into two separate sections.

For species that cannot cross the road, this division creates two isolated habitats. Over time, further development follows—more roads are built, and parts of the forest are cleared for agriculture or urbanization.

As these new land uses do not support the original forest species, the available habitat for those species continues to shrink.

As development increases, the once-vast woodland becomes a series of small, disconnected patches. These fragments are often far apart, preventing plants and animals from moving freely between them.

This isolation can lead to a decline in species populations, reduced genetic diversity, and, eventually, local extinctions.

For example, highways and urban expansion in areas like the Amazon rainforest and North American woodlands have severely fragmented ecosystems, making it difficult for species to survive and thrive in their original habitats.

Solutions to Habitat Fragmentation

Habitat fragmentation can be addressed through a combination of strategies that aim to restore and connect habitats, promote sustainable land use, and raise public awareness.

Wildlife Corridors and Connectivity

Wildlife corridors are areas that connect fragmented habitats, allowing species to move between isolated patches of habitat. Corridors can take the form of green bridges or underpasses that allow wildlife to cross roads and highways safely. These connections are crucial for maintaining gene flow, enabling species migration, and preventing inbreeding.

In Europe, countries like the Netherlands have created "ecoducts" over highways, enabling animals like deer and boar to move freely across fragmented landscapes. In the U.S., wildlife overpasses in places like Banff National Park in Canada have successfully reconnected habitats for large mammals.

Wildlife crossing creates a safe natural corridor bridge for animals to migrate. Image credit: Bogdan Wankowicz

Protected Areas and Buffer Zones

Designating areas of land as protected reserves is a critical solution for preventing further fragmentation.

Governments and conservation organizations can establish protected areas or national parks, preventing development and deforestation in key biodiversity hotspots. Buffer zones around these areas can further prevent urban encroachment and provide a transition between protected habitats and human activities.

The Amazon Rainforest, while still under threat, is home to various protected regions that limit deforestation and maintain large, contiguous ecosystems essential for diverse species.

Habitat Restoration and Reforestation

Restoring degraded or destroyed habitats can reconnect fragmented landscapes and expand the available habitat for species.

Reforestation efforts can rebuild ecosystems that have been cleared for agriculture or urban development. Along with planting native species, efforts to restore wetlands, grasslands, and forests can also reintroduce key environmental features that support wildlife.

The Atlantic Forest in Brazil has seen successful reforestation projects aimed at restoring critical habitats for species like the golden lion tamarin. In Costa Rica, reforestation and sustainable agriculture initiatives have increased forest cover, reconnecting habitats that had been fragmented by cattle ranching and farming.

Sustainable Land-Use Planning

Thoughtful land-use planning minimizes the impact of human activities on ecosystems and prevents further fragmentation.

Governments and city planners can design infrastructure, such as roads, cities, and agricultural lands, to avoid key biodiversity areas. This includes restricting developments in wildlife migration corridors or using vertical development in urban areas to limit the expansion of cities into natural habitats.

Countries like Germany incorporate biodiversity concerns into their land-use planning, ensuring urban development does not sever critical habitats.

Conservation Easements and Incentives

Conservation easements are legally binding agreements that restrict development on private land to protect habitats.

Landowners, especially in rural or forested areas, can be incentivized through tax breaks or payments to keep their land undeveloped, maintaining contiguous habitats. These agreements prevent the sale of land for industrial or residential development, ensuring long-term habitat preservation.

Sustainable Agricultural Practices

Agriculture is a leading cause of habitat fragmentation, but adopting sustainable practices can reduce its impact.

Farmers can use techniques such as agroforestry, which integrates trees and shrubs into agricultural systems, to maintain biodiversity. Additionally, reducing the need for expansive monoculture plantations by practicing crop rotation and diversified farming can prevent large-scale habitat clearing.

In many parts of Africa and South America, agroforestry is being used to support both biodiversity and local livelihoods by creating agricultural landscapes that blend with natural ecosystems.

Urban Green Spaces and Smart Growth

Incorporating green spaces within urban areas can reduce the negative impacts of urban sprawl on natural habitats.

City planners can design urban areas to include parks, green roofs, and natural spaces that act as mini-habitats within cities, providing refuge for birds, insects, and other species. "Smart growth" strategies that encourage more compact, dense development limit urban expansion into surrounding natural areas.

Cities like Singapore have integrated green spaces and gardens throughout the urban landscape, earning the reputation of a "City in a Garden."

Legislation and Policy

Strong environmental laws and policies can limit habitat destruction and fragmentation on a national or global scale.

Governments can enact regulations that protect biodiversity, limit deforestation, and promote sustainable land use. Policies like the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in the U.S. can protect critical habitats from being fragmented by human development. International agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) can also set goals for habitat preservation across borders.

Many countries have implemented laws that require environmental impact assessments before any large-scale development projects can proceed, ensuring biodiversity concerns are addressed.

Public Awareness and Education

Educating the public about the consequences of habitat fragmentation and the importance of biodiversity conservation is essential for long-term success.

Environmental campaigns, school programs, and media can raise awareness of the effects of fragmentation and the steps individuals and communities can take to reduce it. Promoting sustainable lifestyles, reducing resource consumption, and supporting conservation efforts can all help mitigate fragmentation.

Non-governmental organizations like the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) run public awareness campaigns that highlight the impact of habitat destruction and promote sustainable choices for consumers.

Technological Solutions

Advances in technology can aid in monitoring, preventing, and reversing habitat fragmentation.

Tools like satellite imagery, drones, and GIS mapping can track habitat loss and fragmentation in real time, allowing for more targeted conservation efforts. Additionally, technologies like wildlife tracking devices can monitor species' movements and identify where corridors or protected areas are most needed.

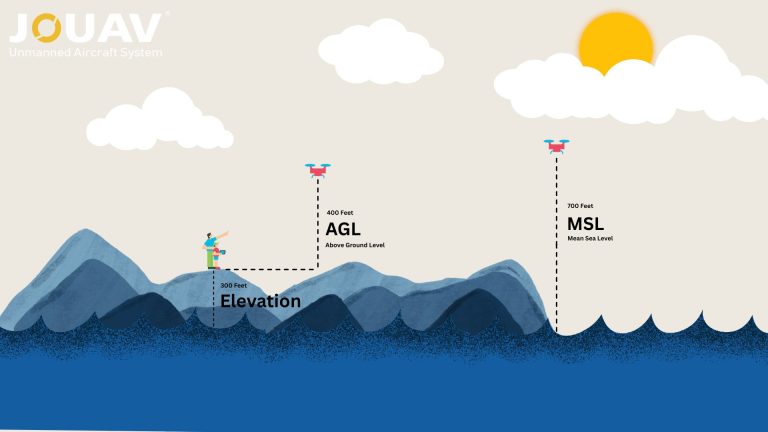

How Are Drones Used for Monitoring Habitat Fragmentation?

Drones have revolutionized the field of habitat fragmentation monitoring, offering unprecedented capabilities for data collection and analysis. Their ability to capture high-resolution aerial imagery and data over large areas provides significant advantages over traditional ground-based methods.

Detailed Habitat Mapping

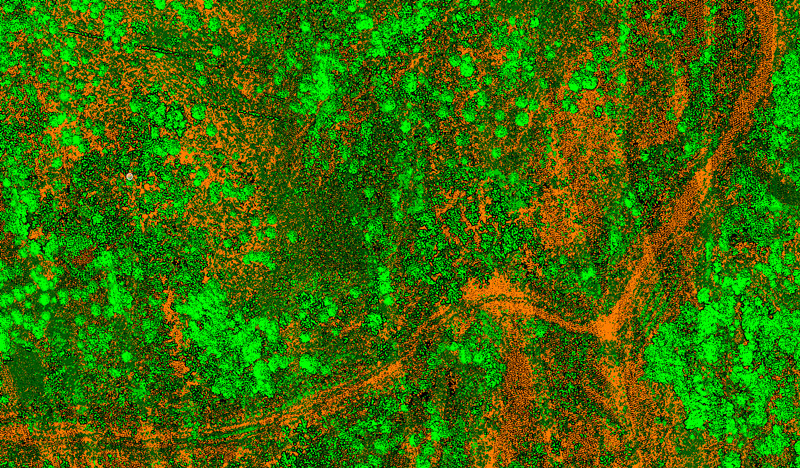

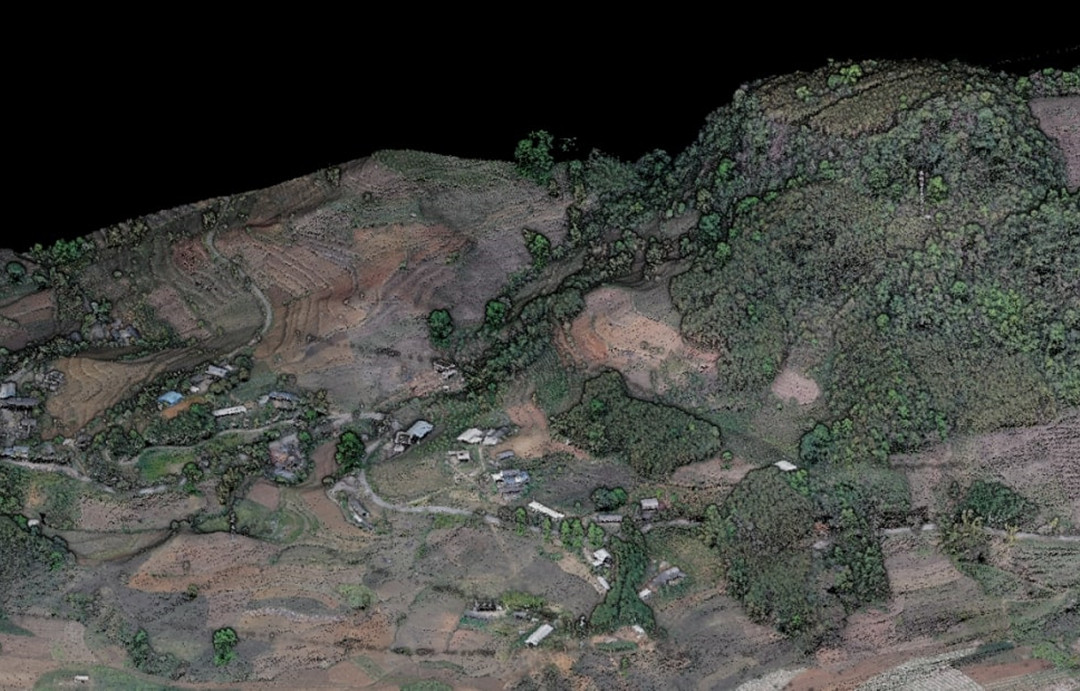

Drones can capture detailed aerial photographs that can be used to create accurate maps of vegetation cover, land use, and habitat boundaries.

By analyzing this imagery, researchers can identify the distribution and abundance of different species within fragmented landscapes and assess the quality of habitats by identifying factors such as invasive species, erosion, and habitat degradation.

Monitoring Fragmentation Over Time

By conducting repeated drone flights over time, researchers can monitor changes in habitat fragmentation, such as the growth of urban areas or the expansion of agricultural land.

Drones can also help identify areas of habitat loss and degradation, such as deforestation or wetland drainage, and track the progress of habitat restoration efforts.

Tracking Wildlife and Connectivity

Drones can be used to monitor the distribution and abundance of species, especially those that are difficult to track using traditional methods. By analyzing drone imagery and GPS tracking data, researchers can study how species use fragmented habitats and identify critical areas for conservation.

Additionally, drones can help assess the connectivity between fragmented habitats by identifying potential barriers to species movement, such as roads or fences.

![]()

Assessing Habitat Health

Drones can be used to study the effects of habitat fragmentation on edge habitats, which often experience different environmental conditions than the interior of fragments.

By analyzing drone imagery, researchers can assess the overall health of habitats, including factors such as vegetation density, soil erosion, and water quality.

Detecting Human Encroachment

Drones can be used to detect illegal activities such as deforestation, poaching, and mining, which can contribute to habitat fragmentation.

Additionally, drones can help monitor the expansion of urban areas and identify areas where development is encroaching on natural habitats.

Supporting Habitat Restoration

Drones can be used to track the progress of habitat restoration efforts and assess their effectiveness.

By identifying challenges to habitat restoration, such as invasive species or soil erosion, drones can help inform conservation strategies and improve restoration outcomes.

Measuring Environmental Changes

Drones can be used to monitor the impacts of climate change on fragmented habitats, such as changes in vegetation cover, water availability, and species distribution.

Additionally, drones can be used to assess the damage caused by natural disasters, such as wildfires, floods, or hurricanes, and to support recovery efforts.

The JOUAV's CW-25E VTOL drone is a highly efficient tool for monitoring habitat fragmentation, offering 210 minutes of flight time, a 100km operating radius, and a 6kg payload capacity.

It supports various sensors, including ortho cameras, LiDAR, multispectral, and hyperspectral cameras, with customizable payload options.

In Yunnan Province, the CW-25E equipped with JoLiDAR-LR22S surveyed 950km² of forest in just 480 minutes, significantly reducing time, cost, and manual labor risks. Read More >>

A team of four can now complete 800km² of forest surveys per day, reaching 15,000km² monthly—a 100-fold efficiency boost over traditional methods. This drone's capability makes it vital for large-scale, precise habitat assessments.

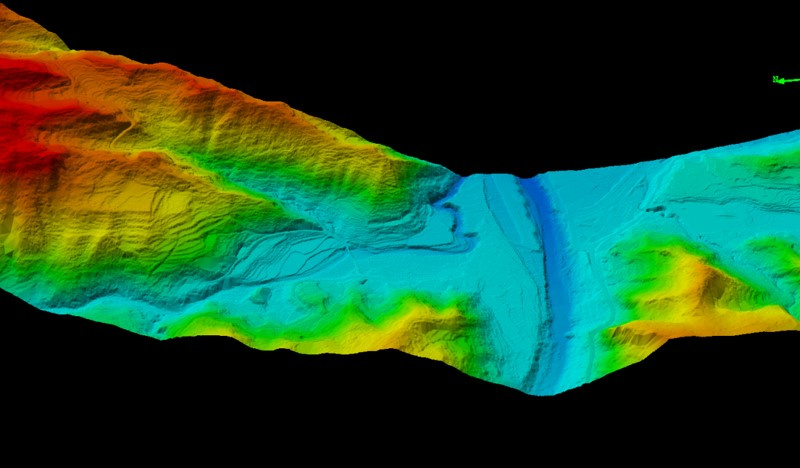

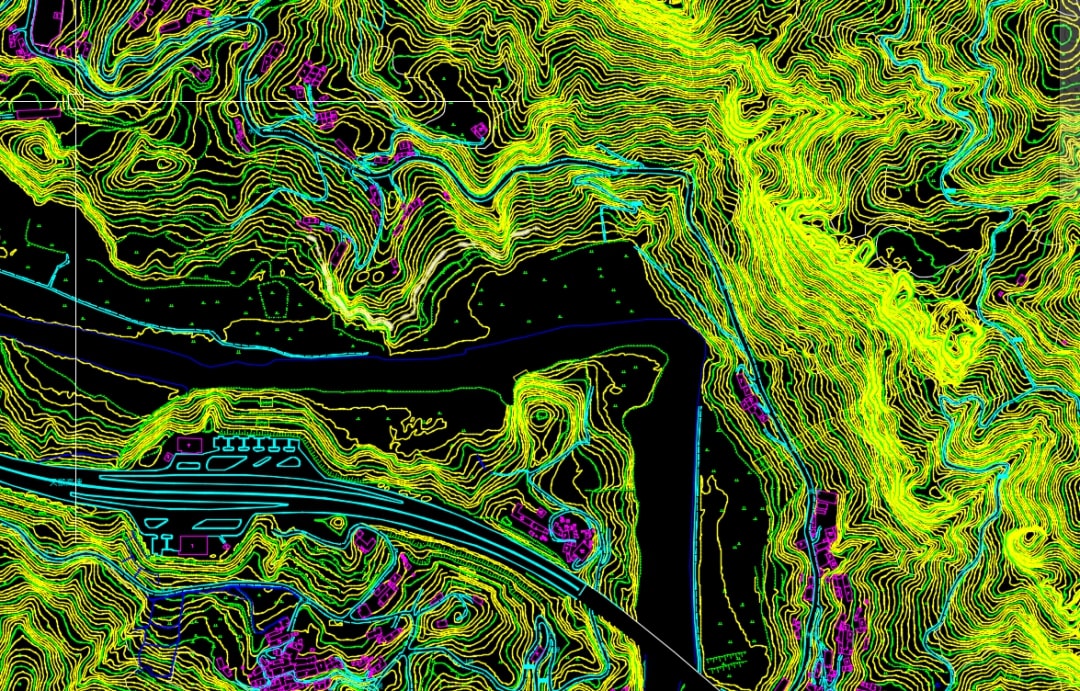

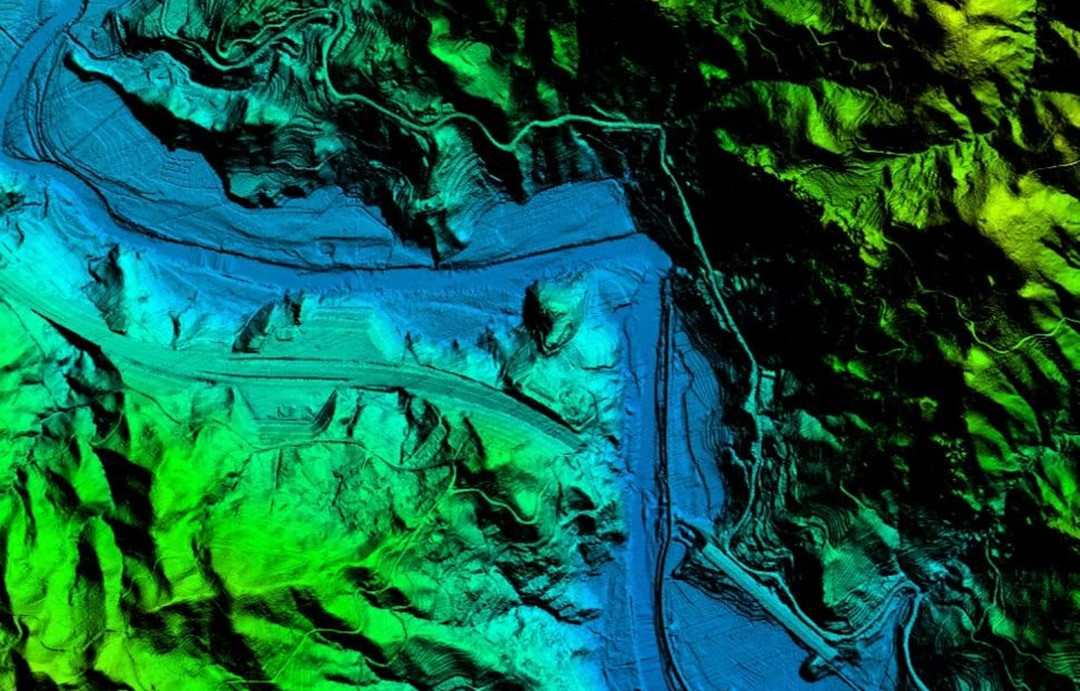

3D point cloud

DLG

DEM